From Greek "Techno", meaning "art" or "skill", and "Logos", meaning "word", "technology" literally means "words concerning skill".

Of course English-speakers don't use it that way today. According to my research, this word entered our language around 1610, and initially translated as "systematic treatment of an art, craft, or technique" - i.e., a treatise or discussion of a specific art or skill. It wasn't used to mean "science of the mechanical and industrial arts" until about 1859, and the term "high technology" - high-tech - doesn't appear until the 60s.

Cast your mind back. 18th century writers might apply the term "art" or "artifice" to express what we mean today when we say "technology"; in the 19th century one might say "industry"; and as recently as the 1950s or even later, you'll often see the term "industrial arts" applied to, say, high school classes which might today be called "tech ed". I think that today, most of the time, when we say "technology", what we really mean is "engineering", or at least the products thereof; we're talking about the creative solving of technical problems, and the objects or techniques which come out of that process.

Perhaps, in the modern context, there's also a sense that technology is synonymous with progress - especially when we add the word "advanced" - "advanced technology" implies better technology, or technology which is further along some kind of understood chronological continuum. I believe we think this way because we stand, right now, at the end of more than a hundred years of extremely rapid development in many areas of science, engineering, and medicine - we have a clear example in our recent past, in our Western society, of the passage of time equaling technological development, and can cavalierly make statements like "in 1900 most people still rode horses, but in 2013 we can orbit the Earth."

Lord Kelvin, who in 1902 famously said:

"No balloon and no aeroplane will ever be practically successful."

But as heady as that kind of "progress" might be, it's also kind of terrifying. I was born in the 1980s, and so I am intimately acquainted with the notion that by the time I have grandchildren, I pretty much won't recognize the world. Many generations all across the late 19th through early 21st centuries have encountered that phenomenon - things change fast in today's world, and that mostly seems to be due to all the widgets and doodads we obsess ourselves with. Consider what 175 years of technological progress might have looked like in, say, the Middle Ages: four generations might live and die in the same village, without anything changing much, as far as the way people did what they did. Not to say that technology didn't change society in the Middle Ages - but the rate of change was dramatically slower than it is today. Traditions survived from generation to generation, which is how they became deeply ingrained in society. They didn't have to adapt, because very little changed.

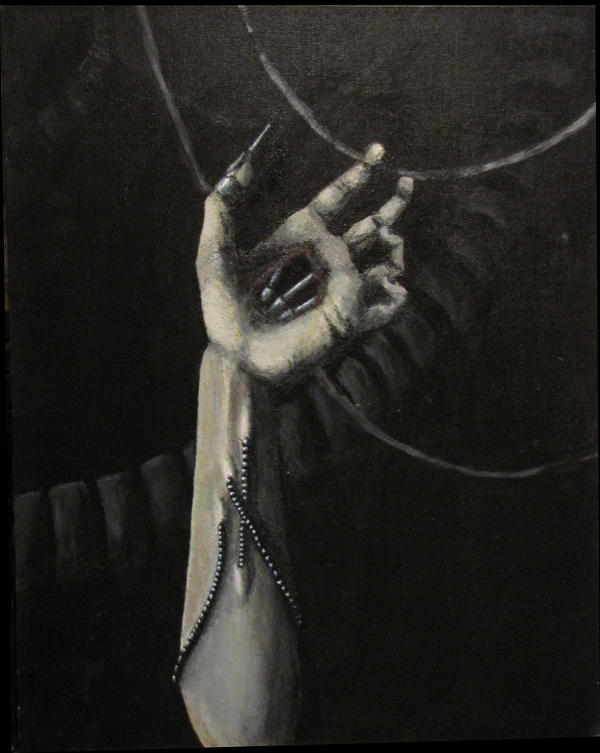

Now we live in a world of constant change, and many of us are killing ourselves trying to keep up. I've had a chance to witness this in many contexts: grandparents seemingly unable to communicate with grandchildren, or grown adults breaking down emotionally when faced with a new phone or computer, or companies, school districts, and governments breaking the bank just to equip their members with the latest tablet. When one takes a step back, it all seems so insane. It seems as if an outside force has begun to afflict humanity: a force of wires and switches, of electrons and radio signals, of silicon chips and water-cooled mainframes.

I think in many cases, we see technology as a menacing Force with a will of its own - something we are helpless in the face of, something which will crush us if we don't learn how to appease it. Change can engender fear, and fear can cause something mundane to appear as a Colossus. I think that sometimes, we believe the Rise of the Robots has begun.

What I feel we have to remember is this: those robots would not exist without us.

Smartphones are handy technological devices. Many of them can do practically anything you need them to, as long as that need is computing, communication, or information-related. Most of them used to have integral, physical keyboards - this, in fact, was the initial selling point which helped the BlackBerry company snag a huge sector of the smartphone market.

But physical keyboards are out of favor in smartphones. Why? No reason at all - except economics. One of the most popular and visible brands in the industry - the iPhone - has no physical keyboard, and by the kind of follow-the-leader correlation which sometimes drives market economics, most other smartphone-producing companies dropped physical keyboards as an option on their devices.

Does the move away from physical keyboards on smartphones constitute a technological advancement? No. It's nothing more than a preference regarding input. If you doubt me, just think hard about how often your "autocorrect" function actually gets it right.

The point here is that technology changed, it changed the way people do things - but the change was not necessary, not irrefutably logical, and driven by very human forces - namely, money. Technology, in this case, is not out of our control - it is a profoundly human force.

As I write this, it's been almost 40 years since humans last walked on the Moon. This fact - that we've never gone back - has often been evinced as an argument for why we never went in the first place. The assumption is that technology moves "forward" chronologically - that once we've done something once, we will only ever do it easier and more cheaply as time passes and techniques improve. Ergo, if we've been to the Moon once, we must be able to do it again, and often; therefore, we never went in the first place.

Wrong.

Recall who it was that said "We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard" - that's right, it was this guy:

And guess who it wasn't? That's right, this guy:

Now, which of the above two gentlemen was in office when Apollo 11 landed? Sadly, it was not dear John, who died before he could see his pet initiative come to fruition. Nixon was the one who called Armstrong and Aldrin on the phone to congratulate them, in what I've always amused myself by thinking must have been a damn bitter pill to swallow. "Hello boys, congratulations on stunning the world by pulling off the culmination of my predecessor and bitter political rival's most enduring legacy." Ouch.

Within two years of Apollo 11's historic flight, the final three missions of the Apollo program - the originally projected Apollos 18, 19, and 20 - were scrapped, or their assets reassigned for other purposes (such as Skylab). Nixon - and Congress - decided that, the stunt having been successfully carried off, there was no need to continue to spend what in modern terms would be over $12 billion annually. That's how Nixon's government saw lunar exploration: an expensive stunt, championed by a predecessor and former bitter rival; a chapter to close, rather than a springboard to new advancements and new discoveries.

In the early 70s, NASA was still planning for crewed Mars missions in the early 1980s, using nuclear thermal rocketry as its main propulsion (a technology which has been thoroughly tested on Earth, yet never used in space). Given the money, they certainly would have attempted it. But Nixon and Congress earmarked that money for the Space Shuttle instead - a project they deemed more economically feasible, and, I'm sure, to some extent, more "Nixon" and less "Kennedy" in spirit.

Again, we see money - and also ego - being the main forces behind an era of technological change - in this case, holding back technological advancement. Technology didn't progress linearly - the engineers focused on its development simply changed their course, according to what was politically and financially feasible.

Technology was not a force unto itself - it fell prey to the whims of the humans who controlled it.

In closing, I'll restate my opening: Technology is just a word, a word whose meaning has fluctuated a lot over the centuries. Our attitude toward technology also fluctuates; it can be an aid or a curse, a boon or a menace, something which will save us, corrupt us, or destroy us. These don't have to be purely esoteric or geeky concepts - you don't need to look to Asimov or Kurzweil to help form your attitudes here. Just think about how it makes you feel to try and set up a new computer, or figure out a new app on your tablet, or get your BlueTooth devices to talk to each other.

These are all tools - tools crafted by humans, to extend our capabilities. At least, that's what they should be - all too often, the main concern is not to extend capabilities, but to extend the bank accounts of executives, or the political capital of politicians. Technology doesn't just happen in a lab or a computer - it's a product of the money which funds that lab, the mind that designed that computer. Without us there would be no technology. Even if Skynet rises from our ashes to dominate the world, it and all its descendants will owe their existence - their very form - to us.

Which may not necessarily be a comforting thought, but it might help you survive your next frustrating encounter with your iPad.